| Citation: | Hao-Nan Sha, Yang-Ming Lu, Ping-Ping Zhan, Jiong Chen, Qiong-Fen Qiu, Jin-Bo Xiong. 2025. Beneficial effects of probiotics on Litopenaeus vannamei growth and immune function via the recruitment of gut Rhodobacteraceae symbionts. Zoological Research, 46(2): 388-400. DOI: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2024.364 |

Probiotic supplementation enhances the abundance of gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae species, critical symbionts contributing to the health and physiological fitness of Litopenaeus vannamei. Understanding the role of Rhodobacteraceae in shaping the shrimp gut microbiota is essential for optimizing probiotic application. This study investigated whether probiotics benefit shrimp health and fitness via the recruitment of Rhodobacteraceae commensals in the gut. Probiotic supplementation significantly enhanced feed conversion efficiency, digestive enzyme activity, and immune responses, thereby promoting shrimp growth. Additionally, probiotics induced pronounced shifts in gut microbial composition, enriched gut Rhodobacteraceae abundance, and reduced community variability, leading to a more stable gut microbiome. Network analysis revealed that the removal of Rhodobacteraceae nodes disrupted gut microbial connectivity more rapidly than the removal of non-Rhodobacteraceae nodes, indicating a disproportionate role of Rhodobacteraceae in maintaining network stability. Probiotic supplementation facilitated the migration of Rhodobacteraceae taxa from the aquatic environment to the shrimp gut while reinforcing deterministic selection in gut microbiota assembly. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that up-regulation of amino acid metabolism and NF-κB signaling pathways was positively correlated with Rhodobacteraceae abundance. These findings demonstrate that probiotic supplementation enriches key Rhodobacteraceae taxa, stabilizes gut microbial networks, and enhances host digestive and immune functions, ultimately improving shrimp growth performance. This study provides novel perspectives on the ecological and molecular mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of probiotics on shrimp fitness.

Litopenaeus vannamei is the predominant shrimp species cultivated worldwide, with annual yields surpassing 5.8 million tons (FAO, 2022). However, the rapid intensification of aquaculture is increasingly challenged by the rising prevalence and severity of shrimp diseases, leading to substantial economic losses each year (Han et al., 2020). Antibiotics are commonly used to prevent and treat infectious diseases, particularly in small-scale aquaculture facilities in developing countries. However, the escalating threat of antibiotic resistance and associated health risks necessitates the establishment of alternative disease management strategies (Defoirdt et al., 2011; Sha et al., 2025), especially given the lack of a vertebrate-like adaptive immune system in shrimp, which complicates vaccine development (Falaise et al., 2016). Under such constraints, probiotics have emerged as a promising approach in sustainable aquaculture (Newaj-Fyzul et al., 2014).

The gut microbiota, often referred to as the “second genome”, plays an integral role in nutrient digestion, immune modulation, and host development (Holt et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2024). Modulating gut microbial composition offers a potential strategy to improve the health, growth, and survival of aquatic animals (Merrifield & Ringo, 2014; Sha et al., 2024). Increasing evidence indicates that probiotic supplementation alters the diversity and structure of shrimp gut microbiota, particularly promoting the proliferation of heterotrophic bacteria, such as Rhodobacteraceae species (Chien et al., 2020; Du et al., 2022). Global meta-analyses of L. vannamei gut microbiota consistently demonstrate that Rhodobacteraceae is a dominant bacterial family across shrimp life stages and represents a core commensal group essential for maintaining host health and growth (Cornejo-Granados et al., 2018). Indeed, gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae species perform critical functional roles, including the production of antibacterial compounds (D'Alvise et al., 2014) and biosynthesis of vitamins (Sonnenschein et al., 2017), among other metabolic processes (Xiong et al., 2024). Moreover, Rhodobacteraceae members have been identified as keystone species that contribute to the stability of shrimp gut microbial networks (Guo et al., 2022). The abundances of Rhodobacter and Ruegeria, two genera within Rhodobacteraceae, are positively associated with improved shrimp growth and survival (Guo et al., 2020; Sha et al., 2024). These findings suggest that the beneficial effects of probiotics may be mediated through the selective recruitment of specific bacterial taxa. Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms by which probiotic supplementation regulates shrimp gut microbiota, especially core and keystone Rhodobacteraceae taxa, is essential for optimizing probiotic applications in aquaculture.

Gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae species are frequently enriched in hosts experiencing environmental stress (Copetti et al., 2021), suggesting their potential role in enhancing host adaptation. Studies have demonstrated that glucose addition induces the aggregation of Rhodobacteraceae species and promotes their migration from the aquatic environment to the shrimp gut, ultimately improving aquaculture performance (Dong et al., 2023). A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms governing bacterial dispersal from surrounding environments into the host gut, particularly in aquatic organisms, is essential for microbiome regulation (Xiao et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2018). The neutral community model has been widely applied to evaluate the contribution of dispersal processes in shaping microbial communities (Zhou & Ning, 2017). This model estimates stochastic processes by analyzing the relationship between the occurrence frequency of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) in local communities and their relative abundance in the broader metacommunity (Östman et al., 2010). ASVs that differ significantly from neutral model predictions are considered to be either selectively favored or opposed by the local community (Xiong et al., 2017). Using this framework, studies have shown that Rhodobacteraceae taxa in seawater can colonize and adapt to the shrimp gut microenvironment, where they are actively selected by larval shrimp (Wang et al., 2020a). Given the ecological significance of Rhodobacteraceae in gut microbiota assembly, further investigation is needed to elucidate how probiotic intervention modulates their recruitment and functional contributions, providing a foundation for optimizing probiotic strategies in shrimp aquaculture.

The gut microbiome modulates host gene expression, influencing host immunity and metabolism through complex host-microbe interactions (Nichols & Davenport, 2021). For example, probiotic Bacillus subtilis promotes the expression of immune-related genes in shrimp, including heat shock protein 70, penaeidin-2b, and β-1,3-glucan binding protein (Chien et al., 2020). Similarly, supplementation with Rhodovulum sulfidophilum has been shown to stimulate the expression of myosin heavy chain b, thereby promoting shrimp growth (Koga et al., 2022). These findings suggest that probiotic-induced gene expression in shrimp follows a strain-specific pattern (Richards et al., 2019). The Rhodobacteraceae family, one of the nine most widely distributed bacterial lineages in marine habitats, comprises over 190 genera and 300 species (Simon et al., 2017). This bacterial group exhibits extensive metabolic, phenotypic, and genotypic diversity. For example, Labrenzia species produce medium-chain fatty acids that enhance oyster immunity (Amiri Moghaddam et al., 2018), while members of the Ruegeria genus synthesize vitamin B12, which supports shrimp growth (Cooper & Smith, 2015). Given this functional diversity, exploring the complex interactions between gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae and host gene expression may provide crucial insights into the molecular mechanisms through which probiotics improve shrimp health.

In our recent work, four probiotic strains with high anti-Vibrio efficiency were successfully isolated from healthy shrimp, with probiotic supplementation shown to significantly enrich Rhodobacteraceae in the shrimp gut (Sha et al., 2024). However, the ecological and molecular mechanisms linking Rhodobacteraceae enrichment to shrimp health and fitness remain to be explored. To address this gap, this study aimed to: (i) determine how probiotic supplementation influences the Rhodobacteraceae community and the stability of the shrimp gut microbiota; (ii) assess whether probiotic supplementation facilitates the migration of Rhodobacteraceae taxa from rearing water into the shrimp gut and the ecological processes governing this transition; and (iii) investigate the complex interplay among probiotics, gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae, host gene expression, and shrimp growth performance.

Four probiotic strains, Ruegeria lacuscaerulensis (Rl), Nioella nitratireducens (Nn), Bacillus subtilis (Bs), and Streptomyces euryhalinus (Se), with antagonistic activity against shrimp white feces syndrome (WFS) were isolated from the gut of healthy L. vannamei (Sha et al., 2024). Each strain was harvested by centrifugation at 3 000 ×g and 4℃ for 5 min, followed by resuspension in 0.9% sterile saline. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of each probiotic suspension was adjusted to 1.0 (109 colony forming units (CFU)/mL). A probiotic consortium was formulated based on the natural abundance ratios of these strains in the gut of healthy shrimp (Rl:Nn:Bs:Se=4:3:2:1). The final concentration of probiotics in the diet was adjusted to 1×107 CFU/g by evenly coating a commercial diet with the probiotic mixture.

In total, 600 healthy L. vannamei larvae (mean weight 0.62 g) were obtained from a commercial farm in Zhejiang, China (N29°32′, E121°31′). The shrimp were randomly distributed across 12 aquaria (30 L each), with 50 individuals per aquarium and six replicates per treatment. Following a 7 day acclimation period on a commercial basal feed, shrimp in the control group (CK) continued receiving the basal diet (Supplementary Table S1), while those in the probiotics-added (PA) group were fed the same diet supplemented with probiotics for an additional 14 days. Shrimp were fed twice daily (10:00h and 16:00h) at a feeding rate of 3.0% of body weight. To maintain optimal water quality, uneaten feed and fecal matter were siphoned before each feeding, and 10% of the rearing water was exchanged every three days.

Shrimp samples were collected at the start (day 0) and end (day 14) of the experiment. Additionally, rearing water samples were obtained on day 14 to evaluate the influence of planktonic bacteria on shrimp gut microbiota (Supplementary Table S2). Hepatopancreatic tissues were collected on day 14 for enzyme activity analysis. The feed conversion ratio (FCR) was determined using the following equation:

|

FCR(%)=Totalfeedintake(g)Finalshrimpweight(g)−Initialshrimpweight(g)×100 |

(1) |

The activities of digestive enzymes (pepsin and lipase) and immune enzymes (alkaline phosphatase, lysozyme, and peroxidase) in the hepatopancreas were determined using commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the protocols suggested by the manufacturer.

Shrimp gut tissues were dissected using sterile forceps. To ensure sufficient DNA yield and minimize individual variability, gut tissues from three shrimp within the same tank were pooled into a single biological sample. To assess microbial biomass, 0.5 L of rearing water from each tank was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane (Millipore, USA). Genomic DNA was then extracted with a Fast DNA Spin Kit (MOBIO Laboratories, USA) following the provided protocols. DNA concentration and purity were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, USA).

In total, 18 shrimp gut samples and 12 water samples were subjected to sequencing. The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified in duplicate using the primers 341F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3’) and 806R (5’-CTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplicons were pooled, purified using a PCR Fragment Purification Kit, and quantified using a PicoGreen-iT dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, USA). Equimolar amplicons from all samples were pooled and sequenced using the NovaSeq PE250 platform (Illumina, USA).

Raw sequencing reads were processed using the QIIME 2 (v.2023.2) (https://qiime2.org/) pipeline (Bolyen et al., 2019). The DADA2 algorithm was employed to filter low-quality reads (Q<20) and denoise reads into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) (Callahan et al., 2016). Taxonomic classification was assigned to each ASV using the “classify-sklearn” package (Pedregosa et al., 2011) against the Silva-138-99 database. ASVs identified as archaea, chloroplasts, mitochondria, or unclassified sequences were removed. Singleton ASVs were also discarded. After quality control, 1 382 109 clean reads were retained across 30 samples, with a mean of 40 085 reads per sample (Supplementary Table S2). To account for variations in sequencing depth, reads were rarefied to a minimum depth of 16 019 sequences per sample.

Total RNA was extracted from 12 biological gut samples collected on day 14 (Supplementary Table S2) using TRIzol reagent, following the manufacturer’s guidelines. RNA concentration and integrity were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. RNA purity was further confirmed by measuring the 260/280 absorbance ratio, ensuring values of 1.9 or higher. mRNA was isolated using oligo (dT) magnetic beads and fragmented into 100–400 bp segments using an ultrasonicator. mRNA was subsequently reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA using an MGIEasy RNA Directional Library Prep Set Kit. The cDNA fragments were diluted to a concentration of 200 ng/μL before the addition of sequencing adapters. Sequencing was conducted using the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, USA).

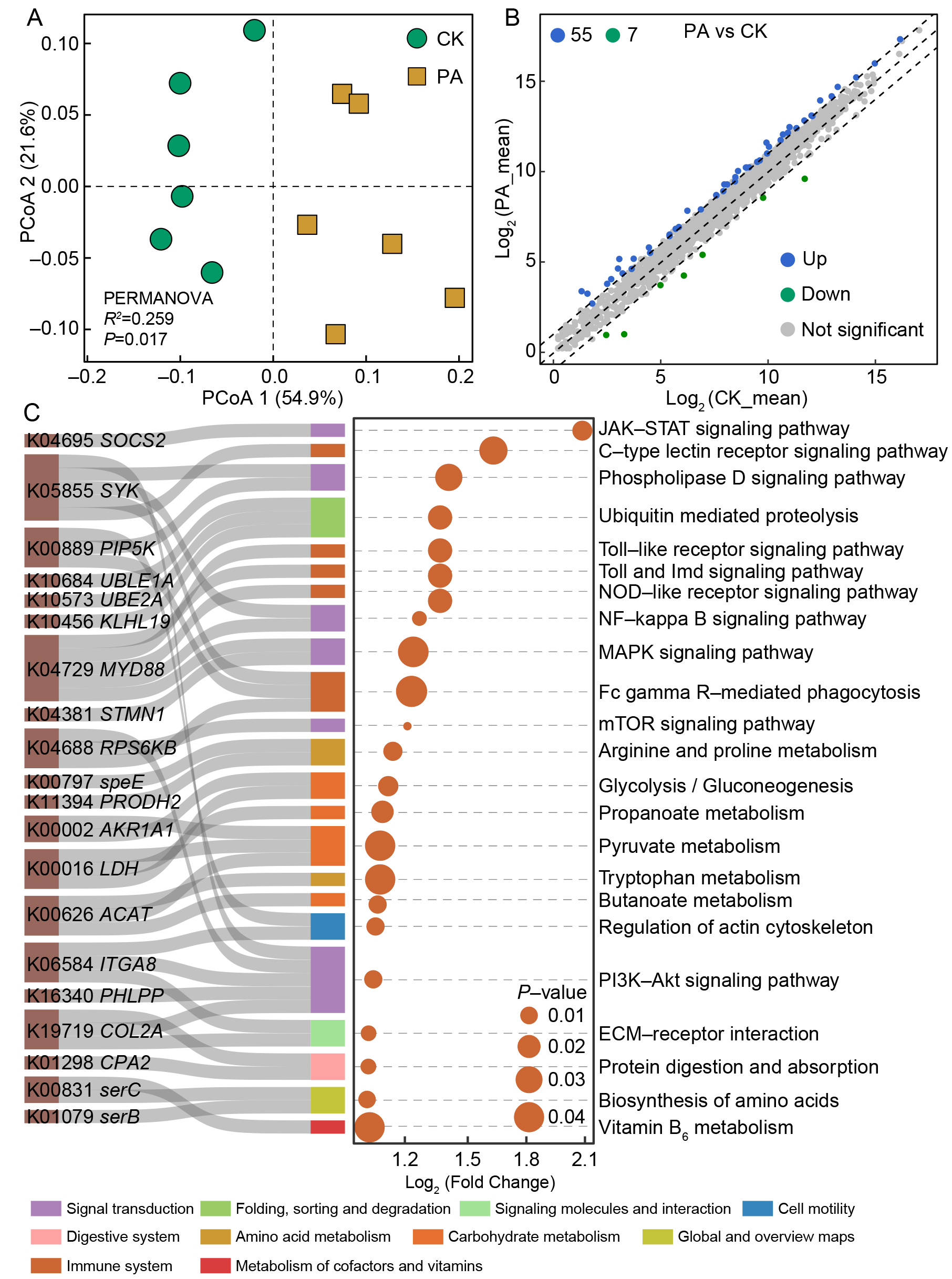

Raw sequencing data were evaluated and processed using FastQC (v.0.11.6) (Brown et al., 2017). After eliminating adaptors, contaminants, and low-quality reads, the remaining reads were mapped to the L. vannamei reference genome (NCBI Accession No. ASM378908v1) (Zhang et al., 2019) using HISAT2 (v2.2.1) (Kim et al., 2019). The DESeq2 package (Love et al., 2014) was utilized to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the CK and PA cohorts, with the thresholds set at a false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05 and |log2 Fold Change|≥1. Functional enrichment analyses were performed by mapping DEGs to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database to identify key biological functions and signaling pathways.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R v.3.6.3, unless otherwise specified (R Core Team, 2016). Both α-diversity (Shannon’s diversity index and observed ASVs) and β-diversity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) were calculated in QIIME2 using the diversity core-metrics-phylogenetic script. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was conducted to visualize compositional differences in the overall bacterial community and the Rhodobacteraceae subset across shrimp gut and aquaculture water samples. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted to assess the relative contribution of probiotic supplementation on variances in bacterial community structure (Dixon, 2003). To predict the sources of gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae on day 14, SourceTracker was used with default parameters (Knights et al., 2011). Gut microbiota on day 14 were designated as the sink, while rearing water bacteria from day 14 and gut microbiota on day 0 were considered potential sources.

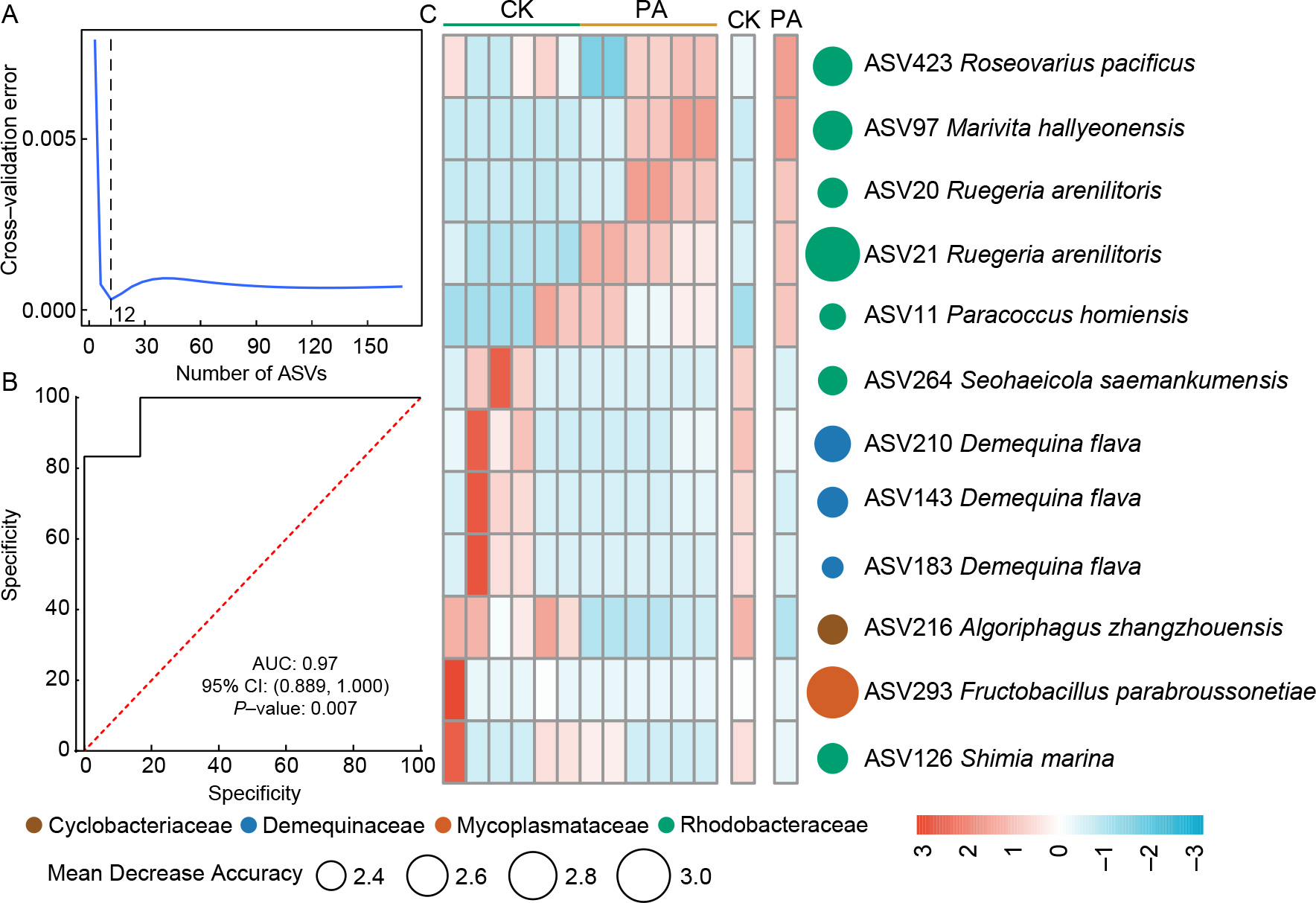

A Random Forest model was implemented to identify ASVs most responsive to probiotic supplementation (Breiman, 2001). The optimal number of features was determined using 10-fold cross-validation with five repetitions, performed using the “rfcv” function (Refaeilzadeh et al., 2009). Model performance was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), with AUC values greater than 0.7 considered indicative of a robust predictive model (Hong et al., 2017).

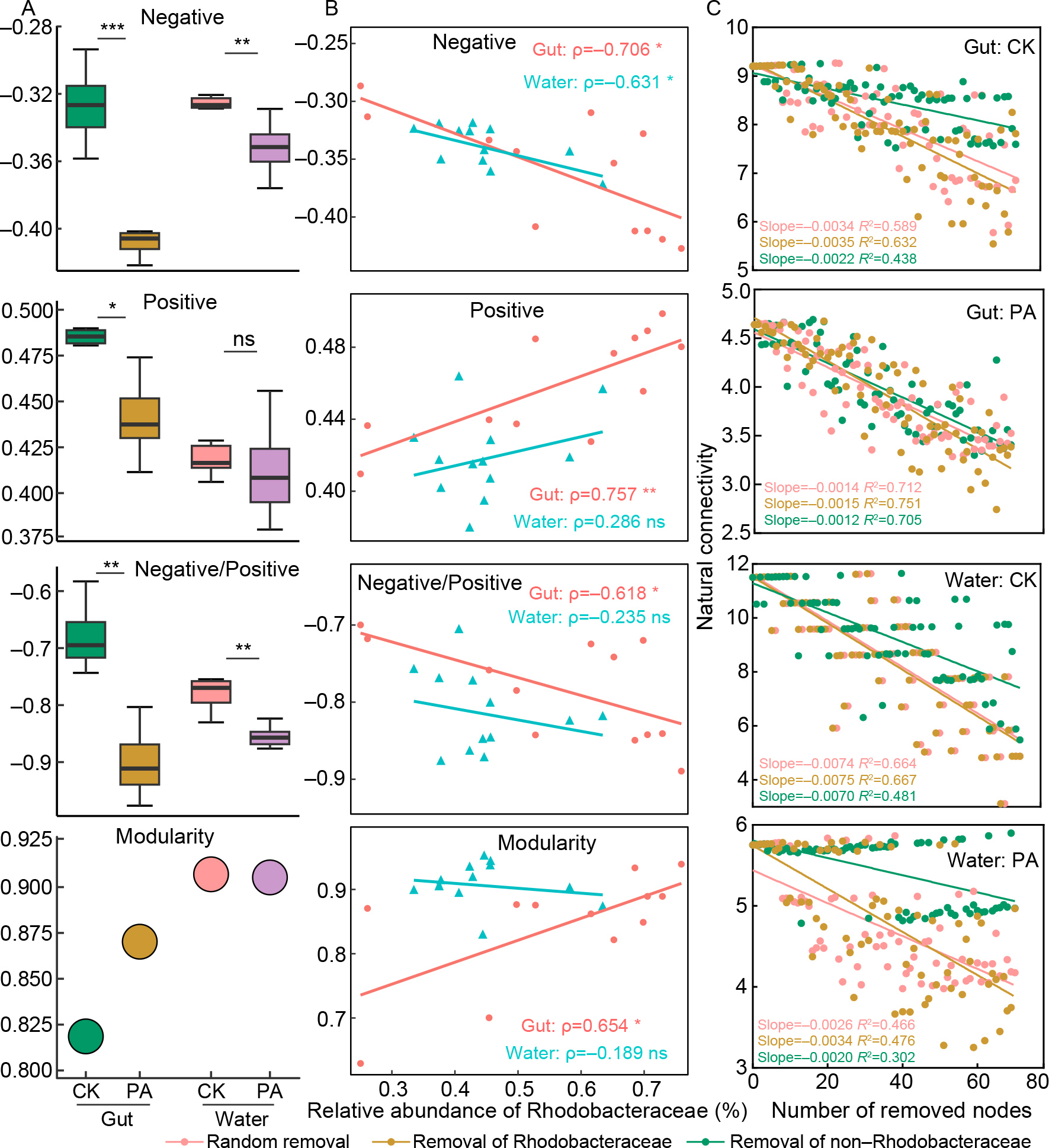

The microbial co-occurrence network was constructed using the “Hmisc” and “igraph” packages (Harrell Jr, 2015). Only highly robust and statistically significant correlations (|r|>0.8, P<0.05) were included in the network. To evaluate network stability, robustness, cohesion, and modularity were calculated. Lower absolute values of negative/positive cohesion and modularity indicate weaker potential competition and reduced network stability (Coyte et al., 2015; Hernandez et al., 2021). Robustness was assessed by measuring the ability of the network to maintain stability after the random removal of target nodes (Montesinos-Navarro et al., 2017). A steeper decline in robustness, represented by a greater absolute slope value in the regression curve, signifies lower network stability (Peng & Wu, 2016). Linear regression was performed to examine the relationships between Rhodobacteraceae relative abundance and network cohesion or modularity using the “Hmisc” package with the “lm” function. In addition, to assess the role of Rhodobacteraceae in network stability, network invulnerability and robustness were further tested by selectively removing Rhodobacteraceae and non-Rhodobacteraceae nodes (Coyte et al., 2015).

To assess shifts in the ecological processes governing the gut Rhodobacteraceae community under the influence of probiotics, a neutral community model (NCM) was applied using Rhodobacteraceae ASVs extracted from the overall bacterial community (Sloan et al., 2006). Model goodness-of-fit (GoF, R2 value) was determined using Östman’s method (Östman et al., 2010), with higher R2 values indicating a greater contribution of stochastic processes. The immigration rate (m) was determined using non-linear least squares fitting (Elzhov et al., 2023). Confidence intervals (95%) for all model parameters were determined via bootstrapping with 1 000 replicates (Sloan et al., 2006).

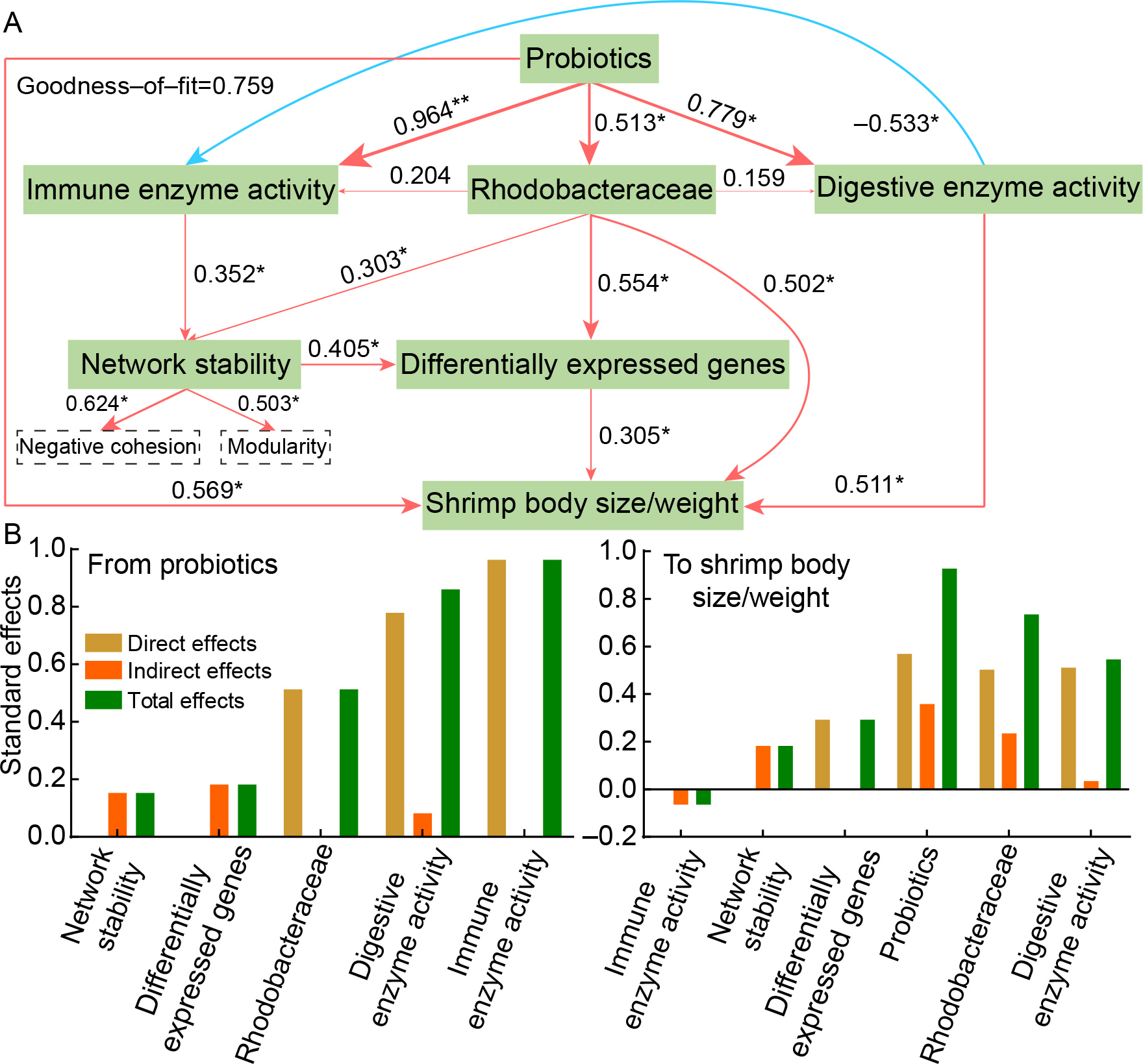

PLS-PM was used to evaluate the complex interactions among probiotic supplementation, gut Rhodobacteraceae community, enzyme activity, overall gut network stability, DEGs, and shrimp growth performance (Sanchez et al., 2024). The model was developed based on the following theoretical assumptions: (i) probiotic supplementation directly alters gut microbial composition and enhances network stability, and (ii) probiotics improve shrimp digestive and immune functions, which synergistically promote growth. Model fit was assessed using the GoF statistic, while path coefficients and coefficients of determination (R2) were computed based on 999 permutations (Sanchez et al., 2024).

Shrimp fed the probiotic-supplemented diet exhibited enhanced growth performance compared to the control group (Supplementary Figure S1A). Among the probiotic strains, Rl, Nn, and Bs were detected in the shrimp gut and were significantly enriched in the PA-treated shrimp relative to the CK group (Supplementary Figure S2). The FCR was significantly lower in PA shrimp than in CK shrimp (Supplementary Figure S1B), corresponding with notable increases in body length (13.1%, P<0.01) and body weight (16.2%, P<0.05) (Supplementary Figure S1C, D). Furthermore, digestive (lipase) and immune enzyme (catalase and alkaline phosphatase) activities were significantly higher in PA shrimp than in CK shrimp (Supplementary Figure S1F–H). However, no significant difference in mortality was observed between the two groups (Supplementary Figure S1J).

Taxonomic classification revealed that Rhodobacteraceae was a dominant bacterial family across all samples. The relative abundance of Rhodobacteraceae in the shrimp gut and surrounding water was 49.1% and 43.9% in the CK group, respectively, increasing significantly to 65.3% and 50.6% in the PA group (Supplementary Figure S3 and Table S3). At the genus level within Rhodobacteraceae, probiotic supplementation significantly increased the relative abundance of Ruegeria in both the shrimp gut and rearing water, whereas Shimia exhibited the opposite trend (Supplementary Figure S4A). The proportion of unique ASVs in the gut was comparable between CK and PA shrimp (Supplementary Figure S4B). However, in the CK group, 48.2% of ASVs were shared between rearing water and shrimp gut, whereas this proportion decreased to 40.5% in the PA group. Conversely, the cumulative relative abundance of shared ASVs in the PA group increased to 83.1%, compared to 79.1% in the CK group (Supplementary Figure S4C). These findings suggest that probiotic supplementation enriched the dominant ASVs shared between shrimp gut and rearing water, particularly Rhodobacteraceae taxa. Notably, more than one-third of these shared ASVs belonged to Rhodobacteraceae, with significant enrichment of Paracoccus and Ruegeria (P<0.05) in PA shrimp compared to CK shrimp (Supplementary Figure S4C and Table S4).

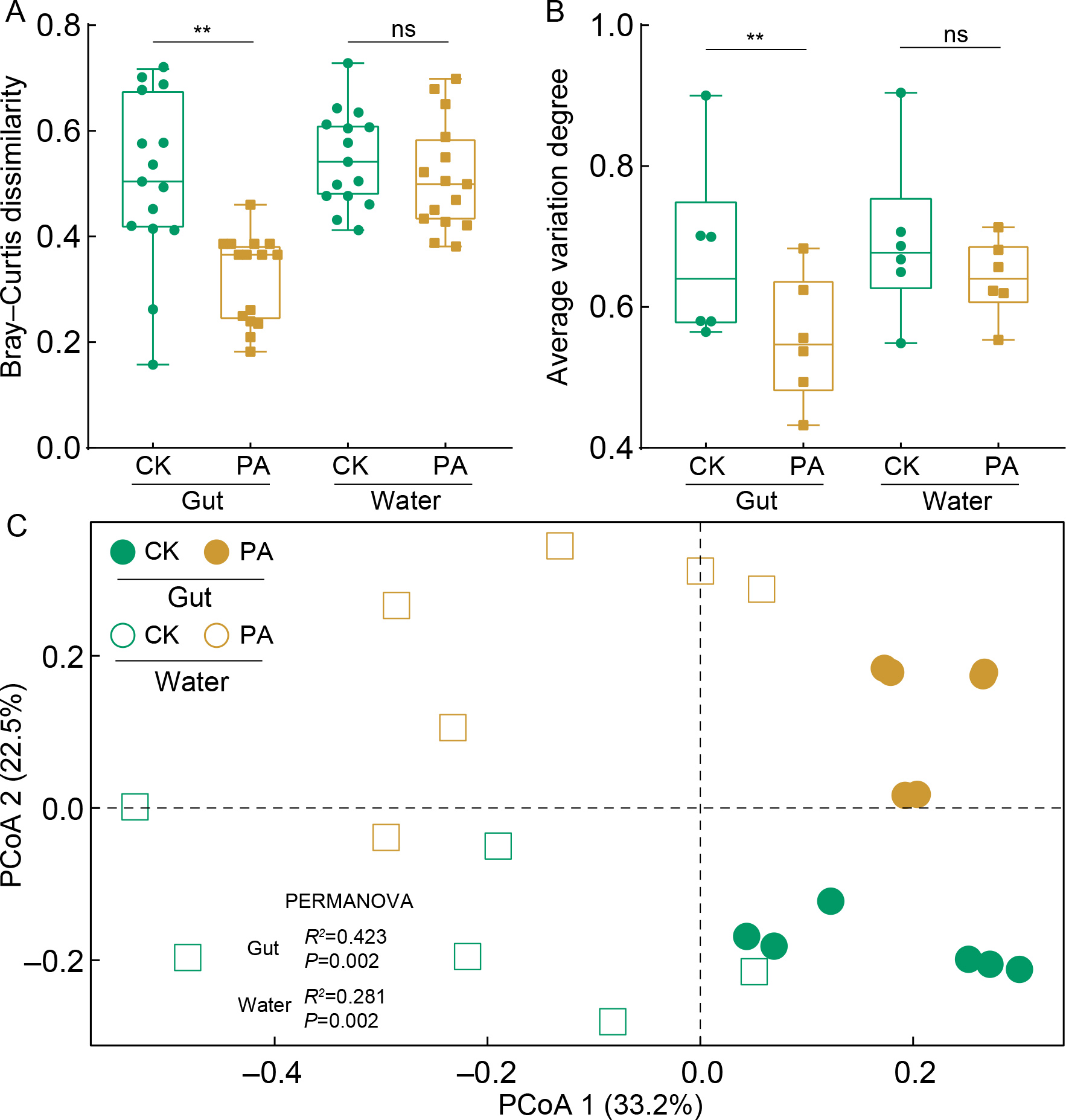

The α-diversity analysis results revealed no significant differences in microbial richness between CK and PA shrimp or rearing water (unpaired t-test, P>0.05) on day 14 (Supplementary Figure S5). However, probiotic supplementation significantly altered gut microbial composition (Figure 1A; Supplementary Figure S6A) and reduced community dissimilarity (P<0.05, Figure 1B, C) for both Rhodobacteraceae and the overall gut microbiota (P<0.05, Supplementary Figure S6B, C) compared with CK shrimp. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in the Rhodobacteraceae community of rearing water (Figure 1B, C).

A Random Forest model was constructed to identify gut biomarkers characterizing probiotic supplementation. Notably, the top 12 discriminatory ASVs, including seven affiliated with Rhodobacteraceae, achieved an AUC of 0.97 (Figure 2A, B). The relative abundances of these 12 biomarkers were significantly altered by probiotic supplementation. For example, ASV423 Roseovarius pacificus and ASV97 Marivita hallyeonensis were significantly enriched in PA shrimp compared to CK shrimp, while ASV143 Demequina flava and ASV126 Shimia marina exhibited the opposite trend (Figure 2C).

Probiotic supplementation significantly improved the negative cohesion, negative-to-positive cohesion ratio, and modularity of the overall gut bacterial network (Figure 3A), as well as those of the Rhodobacteraceae subnetwork (Supplementary Figure S7). In addition, these three topological parameters of the gut microbiota network exhibited strong positive correlations with the relative abundance of gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae (Figure 3B). Overall gut network robustness (resistance to node loss) was assessed by randomly removing nodes. The PA-treated shrimp exhibited higher gut network robustness than the CK group, as indicated by a lower absolute slope in the regression curve (Figure 3C). Additionally, Rhodobacteraceae played a disproportionately significant role in maintaining network stability following probiotic supplementation. The regression slope was steepest in PA shrimp after Rhodobacteraceae node removal, whereas it was lowest when non-Rhodobacteraceae nodes were removed (Figure 3C), highlighting the greater sensitivity of the network to Rhodobacteraceae loss. A similar trend was observed in the rearing water bacterial community (Figure 3). Collectively, these findings indicate that probiotic supplementation strengthens microbiota network stability in both the shrimp gut and rearing water through the enrichment of Rhodobacteraceae taxa.

Probiotic supplementation increased the relative importance of deterministic processes (model fit R2=0.64) governing the overall gut microbiota compared to controls (R2=0.68) (Supplementary Figure S8), suggesting that probiotics potentiated host-driven selection. Among the overrepresented ASVs, Rhodobacteraceae taxa accounted for 57.5% of the microbial community in PA shrimp compared to 54.5% in CK shrimp (Supplementary Figure S8). Overrepresented ASVs are considered potential probiotics due to their higher likelihood of successful colonization in the shrimp gut (Xiong et al., 2018). Therefore, focus was placed on the Rhodobacteraceae community. The model fit for Rhodobacteraceae in CK shrimp was R2=0.42, which increased to R2=0.55 in the PA cohort (Supplementary Figure S9A). In addition, the migration rate (m) of Rhodobacteraceae taxa from rearing water to the shrimp gut was higher in PA shrimp (m=0.010) than in CK shrimp (m=0.008) (Supplementary Figure S9A). This indicates that probiotic supplementation facilitated the transfer of Rhodobacteraceae from the surrounding water into the shrimp gut. In line with this, probiotics reduced the contribution of homogenous selection in structuring the Rhodobacteraceae community (32.0% in PA vs. 60.4% in CK). The role of homogenizing dispersal, which was 1.87% in CK shrimp, was significantly enhanced in PA shrimp, reaching 5.91% (Supplementary Figure S9B). SourceTracker analysis further confirmed that a significantly higher proportion of gut Rhodobacteraceae taxa in PA shrimp originated from the surrounding water compared to CK shrimp (unpaired t-test, P=0.028). Additionally, probiotic supplementation increased the inheritance of Rhodobacteraceae taxa from younger shrimp (individuals on day 0, Supplementary Figure S9C).

As mRNA abundance does not always directly correspond to enzymatic activity, the activity levels of lipase, catalase, lysozyme, and alkaline phosphatase were regressed against the mRNA expression of their corresponding encoding genes. Results showed significant positive associations (Supplementary Figure S10), suggesting that observed transcriptional changes reflect functional enzymatic activity.

A total of 2 946 genes were functionally annotated across 12 shrimp gut transcriptomes on day 14. A clear separation between the CK and PA cohorts was detected (ANOSIM r=0.259, P=0.017) (Figure 4A). Differential expression analysis identified 62 DEGs between the two groups, based on a cutoff of P<0.05 and |log2 FC|≥1 (Figure 4B). Among these, 55 genes were up-regulated in PA shrimp, primarily affiliated with signal transduction, carbohydrate metabolism, and immune system function, while the down-regulated genes were predominantly linked to amino acid metabolism, glycan biosynthesis, and metabolic pathways (Figure 4C).

Procrustes analysis revealed no significant association between the overall gut microbiota and shrimp transcriptomic profile (M2=0.856, P=0.400) (Supplementary Figure S11A). However, a significant correlation was observed between the Rhodobacteraceae community and DEGs (M2=0.660, P=0.037) (Supplementary Figure S11B), indicating that specific gut bacterial populations, such as Rhodobacteraceae, are associated with host gene expression. KEGG pathway mapping of DEGs highlighted two key pathways related to amino acid metabolism (Figure 5A) and immune responses (Figure 5B). Notably, the expression of DEGs within these pathways were positively correlated with five key biomarkers affiliated with Rhodobacteraceae, including ASV11 Paracoccus homiensis and ASV20 Ruegeria arenilitoris (Figure 5C).

PLS-PM effectively captured the interrelationships among probiotic supplementation, digestive and immune activities, gut Rhodobacteraceae community, overall gut network stability, DEGs, and shrimp growth (GoF=0.759, Figure 6A). Probiotic supplementation emerged as the primary driver of improved shrimp growth performance (0.927), exerting both direct (0.569) and indirect (0.358) effects (Figure 6B). Probiotic addition also had a significant positive effect on digestive enzyme activity (0.779), immune function (0.964), and the abundance of gut Rhodobacteraceae (0.513) (Figure 6). The Rhodobacteraceae community contributed substantially to shrimp growth (0.713), driven by both direct (0.502) and indirect (0.211) pathways. Digestive activity also played a crucial role (0.545), including both direct (0.511) and indirect (0.034) effects. Gut microbiota network stability (indirect, 0.182) and DEGs (direct, 0.305) positively influenced shrimp growth, whereas immune enzyme activity did not exhibit a significant indirect effect (–0.064) (Figure 6).

Extensive evidence has demonstrated that probiotics effectively potentiate shrimp growth and immune function by modulating the gut microbiota and inducing immune responses (Fraher et al., 2012; Newaj-Fyzul et al., 2014; Xiong et al., 2024). However, not all gut commensals contribute equally to host fitness. Instead, specific bacterial taxa play disproportionately critical roles in shaping gut microbiome stability and function, independent of their overall abundance (Dai et al., 2019). Identifying these key microbial groups is essential for designing targeted microbiota-based interventions. Given the crucial role of Rhodobacteraceae in promoting shrimp growth (Guo et al., 2022), this study focused on how Rhodobacteraceae taxa influence microbiome structure, host transcriptomic responses, and growth performance under probiotic supplementation.

Probiotic supplementation significantly increased shrimp body weight and length (Supplementary Figure S1C, D). These improvements were likely driven by enhanced digestive enzyme activity, which led to a 19.3% increase in feed conversion efficiency (Supplementary Figure S1B). Previous studies have demonstrated that probiotics promote shrimp growth by optimizing feed utilization (Chen et al., 2021). For instance, dietary supplementation with Bacillus species has been reported to increase the FCR by 16.0% in L. vannamei (Sadat Hoseini Madani et al., 2018) and 15.6% in Penaeus monodon (Boonthai et al., 2011). In addition to growth benefits, probiotic supplementation markedly enhanced shrimp immune responses (Supplementary Figure S1G–I), although this enhancement did not directly improve shrimp growth performance (Figure 6A). This suggests that, in healthy shrimp, probiotics may preferentially direct energy allocation toward growth rather than immune defense. Overall, the formulated probiotic consortium effectively improved shrimp FCR and growth performance. However, as probiotics remain exogenous additives, further research is needed to evaluate their long-term ecological impact, including potential disruptions to native microbial communities and the adaptive responses of pathogenic bacteria to probiotic antagonism.

Probiotic supplementation significantly enriched the abundance of gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae, particularly members of the genera Paracoccus and Ruegeria (Supplementary Figure S4A). Paracoccus species are well-documented producers of astaxanthin, a potent antioxidant (Olmos-Soto & Ruiz, 2012), while Ruegeria is capable of synthesizing B vitamins essential for metabolic and immune functions (Cooper & Smith, 2015). Both astaxanthin and B vitamins play critical roles in shrimp growth and immunity (Zhang et al., 2013; Cui et al., 2016), with dietary supplementation of these compounds shown to enhance shrimp immune responses (Cui et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). Consistent with these findings, the increased abundance of Paracoccus and Ruegeria in PA-treated shrimp was associated with enhanced immune activity (Supplementary Figure S12). Notably, ASV21 Ruegeria arenilitoris and ASV11 Paracoccus homiensis emerged as the most responsive taxa to probiotic supplementation (Figure 2C). Ruegeria arenilitoris harbors quorum-sensing systems that facilitate adaptation to environmental stress (Lee et al., 2011), while Paracoccus homiensis produces carotenoids with antioxidant and antibacterial properties (Jaber & Majeed, 2021). Their increased abundance in PA-treated shrimp likely contributed to improved host fitness. Beyond their metabolic functions, Rhodobacteraceae species are recognized as K-strategists with high resource affinity, favoring the formation of stable microbial communities (Yang et al., 2020). Accordingly, PA-treated shrimp exhibited greater gut microbiota stability (lower AVD) compared to the CK cohort (Figure 1C). Similarly, the enrichment of gut-associated K-strategist bacteria has been linked to improved health and survival in aquaculture species (Vadstein et al., 2018). These findings suggest that probiotic supplementation reshapes gut microbiota assembly in shrimp via Rhodobacteraceae enrichment, leading to a more stable and convergent microbial community structure.

Probiotic supplementation significantly increased negative cohesion while reducing positive cohesion within the overall gut network (Figure 3A), with both parameters strongly influenced by the enrichment of Rhodobacteraceae (Figure 3B). Microbial community stability is closely associated with the prevalence of negative correlations among taxa, as competitive interactions reduce network vulnerability to species loss (Hernandez et al., 2021). Elevated competition among symbionts has been shown to increase gut microbiota stability (Goldford et al., 2018), and Rhodobacteraceae species are known to form competitive networks under fluctuating environmental conditions (Goldford et al., 2018). In line with this, probiotic supplementation promoted competitive interactions among gut Rhodobacteraceae taxa (Supplementary Figure S7A), which may have contributed to enhanced gut network stability. Increased microbial competition has also been associated with higher metabolic activity, potentially enabling aquatic animals to adapt to diverse environmental conditions (Ding et al., 2022). Network invulnerability tests further demonstrated that the removal of Rhodobacteraceae taxa resulted in a more rapid decline in network connectivity in both the shrimp gut and rearing water compared to removal of non-Rhodobacteraceae taxa (Figure 3C). Conversely, the enriched Rhodobacteraceae population significantly strengthened gut network stability (Figure 6). This is consistent with previous findings showing that a higher proportion of core microbes belonging to Rhodobacteraceae improves shrimp gut network stability (Guo et al., 2020). Collectively, these results indicate that probiotic-induced enrichment of Rhodobacteraceae promotes gut microbiota resilience by acting as keystone species that sustain a more stable and invulnerable microbial network in shrimp.

Growing research has shown that the supplementation of exogenous additives, such as molasses and probiotics, directly modulates bacterioplankton communities in aquaculture environments, consequently influencing the composition of gut microbiota in aquatic organisms (Guo et al., 2020; Koga et al., 2022). However, the extent to which exogenous additives drive microbial dispersal from the external environment into the host gut, as well as the underlying mechanisms, remains poorly understood. In this study, probiotic supplementation strengthened the role of deterministic processes in governing the recruitment of microbial taxa from rearing water into the shrimp gut (Supplementary Figure S8). This suggests that shrimp exhibit a stronger selective preference for colonizing external taxa when exposed to probiotic supplementation (Sha et al., 2024). A healthy host actively selects beneficial symbionts during growth, thereby imposing less pressure on the colonization of beneficial species (Tellier et al., 2010). Consistent with this notion, probiotic supplementation significantly stimulated the migration of Rhodobacteraceae taxa from the culture environment into the shrimp gut (Supplementary Figure S9C). A higher migration rate facilitates microbiota homogenization (Evans et al., 2017), leading to a more convergent Rhodobacteraceae community structure (Figure 1B, C). Consequently, PA shrimp acquired a greater proportion of Rhodobacteraceae members from bacterioplankton compared to CK shrimp (Supplementary Figure S8 and Table S3), alongside a shift toward a more stochastic gut Rhodobacteraceae community under probiotic supplementation (Supplementary Figure S9). Despite these findings, the contributions of different species to ecological processes vary, leading to inconsistencies between the assembly mechanisms of the overall community and specific bacterial groups. The underlying mechanisms regulating these disparities remain unclear. For example, in calf fecal microbiota, Actinobacteria abundance is positively correlated with deterministic processes, whereas Firmicutes exhibits the opposite trend (Pan et al., 2024). Similarly, the discrepancy between the assembly processes of the overall shrimp gut community and the Rhodobacteraceae subcommunity suggests that ecological processes are selectively adjusted to support host growth under probiotic supplementation. A recent study demonstrated that a stochastic gut microbiota enhances the resistance of shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus) to external stresses (Zhang et al., 2024). Taken together, these findings suggest that probiotic supplementation increases the deterministic processes governing overall gut microbiota assembly, facilitating the selective recruitment of Rhodobacteraceae taxa from the external environment into the shrimp gut. This, in turn, potentiates the resilience and stability of the shrimp gut microbiome.

The gut microbiota plays a critical role in regulating host growth by modulating transcriptional activity (Wahlström et al., 2016). In this study, probiotic supplementation significantly altered shrimp gene expression patterns. However, the overall gut microbiota composition did not exhibit a strong association with global transcriptional profiles. Instead, DEGs were strongly influenced by the Rhodobacteraceae community (Supplementary Figure S11), underscoring the disproportionate role of Rhodobacteraceae in shaping shrimp physiology. Consistent with this, probiotic supplementation directly enriched Rhodobacteraceae, thereby improving gut network stability and modulating shrimp gene expression (Figure 6). Among the DEGs, probiotic supplementation significantly induced the expression of genes involved in glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism, as well as cysteine and methionine metabolism (Figure 5). These amino acids are essential for growth and immune function in L. vannamei (Wu, 2009; Xie et al., 2014). Lipids serve as crucial energy sources for shrimp, providing necessary substrates for growth through digestion and absorption pathways (Wang et al., 2020b). Notably, sphingolipids play a key role in cell proliferation and differentiation (Xu et al., 2023). In line with this, genes encoding lipid and sphingolipid metabolism were up-regulated (Figure 4B), aligning with the improved performance observed in PA shrimp (Supplementary Figure S1). Additionally, the NF-κB signaling pathway, a central regulator of shrimp immune defense (Hoffmann & Baltimore, 2006), is activated by spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) and myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MyD88) (Chtarbanova & Imler, 2011; Byeon et al., 2012). Probiotic supplementation led to the up-regulation of SYK and MyD88 (Figure 4C), with their expression levels positively associated with increased Rhodobacteraceae abundance (Figure 5C). This is consistent with findings in other marine species, where gut-associated Rhodobacteraceae species positively affect the metabolism and amino acid biosynthesis in swimming crab (Lin et al., 2023) and enhance immune responses via NF-κB activation in sea cucumbers (Yang et al., 2015). In addition, both arginine and proline metabolism are essential for immune regulation (Figure 4B). Dietary supplementation with arginine or proline has been shown to increase the survival rate of shrimp under Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection (Xie et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2024). Overall, probiotic supplementation directly enriches gut Rhodobacteraceae, which further modifies shrimp transcriptomic responses, inducing key metabolic and immune pathways while exerting indirect effects on DEGs (Figures 4–6).

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of how probiotic supplementation improves shrimp fitness by modulating gut microbiota composition and transcriptomic responses. Notably, supplementation significantly improved feed conversion efficiency and promoted shrimp growth. In addition, probiotics induced notable shifts in microbiota, with particular enrichment of Rhodobacteraceae. The ecological mechanisms underlying these changes involved a reduction in homologous and heterogeneous selection pressures on gut commensals, facilitating the migration of Rhodobacteraceae taxa from rearing water into the shrimp gut and promoting microbiota convergence. In addition, gut network stability was disproportionately influenced by Rhodobacteraceae, with network robustness shown to be more sensitive to the loss of Rhodobacteraceae taxa than non-Rhodobacteraceae taxa. At the transcriptomic level, the altered gene expression patterns in shrimp were directly shaped by the gut Rhodobacteraceae community rather than the overall gut microbiota. Collectively, these findings highlight the pivotal role of Rhodobacteraceae in regulating shrimp gut microbial dynamics and physiological responses. This study advances our understanding of the ecological and molecular mechanisms by which probiotics enhance shrimp health, offering insights for optimizing microbiota-based interventions in aquaculture.

The raw sequence reads reported in this study are available from the China National Center for Bioinformation database (GSA: CRA012037), NCBI database (BioProjectID PRJNA1227121), and Science Data Bank database (DOI: 10.57760/sciencedb.j00139.00172).

Supplementary data to this article can be found online.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Experimental design and conception: J.B.X., J.C., and H.N.S.; Investigation: H.N.S., Y.M.L., P.P.Z., and Q.F.Q.; formal analysis: H.N.S. and J.B.X.; writing-original draft: H.N.S.; writing-review & editing: J.B.X. and H.N.S.; experimental organization and supervision: J.B.X. and J.C. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

|

Amiri Moghaddam J, Dávila-Céspedes A, Kehraus S, et al. 2018. Cyclopropane-containing fatty acids from the marine bacterium Labrenzia sp. 011 with antimicrobial and GPR84 activity. Marine Drugs, 16(10): 369. DOI: 10.3390/md16100369

|

|

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, et al. 2019. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nature Biotechnology, 37(8): 852–857. DOI: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9

|

|

Boonthai T, Vuthiphandchai V, Nimrat S. 2011. Probiotic bacteria effects on growth and bacterial composition of black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon). Aquaculture Nutrition, 17(6): 634–644. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2011.00865.x

|

|

Breiman L. 2001. Random forests. Machine Learning, 45(1): 5–32. DOI: 10.1023/A:1010933404324

|

|

Brown J, Pirrung M, McCue LA. 2017. Fqc dashboard: integrates fastqc results into a web-based, interactive, and extensible fastq quality control tool. Bioinformatics, 33(19): 3137–3139. DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx373

|

|

Byeon SE, Yi YS, Oh J, et al. 2012. The role of src kinase in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators of Inflammation, 2012: 512926.

|

|

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, et al. 2016. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nature Methods, 13(7): 581–583. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.3869

|

|

Chen LZ, Lv CJ, Li B, et al. 2021. Effects of Bacillus velezensis supplementation on the growth performance, immune responses, and intestine microbiota of Litopenaeus vannamei. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8: 744281. DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2021.744281

|

|

Chien CC, Lin TY, Chi CC, et al. 2020. Probiotic, Bacillus subtilis E20 alters the immunity of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei via glutamine metabolism and hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 98: 176–185.

|

|

Chtarbanova S, Imler JL. 2011. Microbial sensing by Toll receptors: a historical perspective. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 31 (8): 1734–1738.

|

|

Cooper MB, Smith AG. 2015. Exploring mutualistic interactions between microalgae and bacteria in the omics age. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 26: 147–153. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.07.003

|

|

Copetti F, Gregoracci GB, Vadstein O, et al. 2021. Management of biofloc concentrations as an ecological strategy for microbial control in intensive shrimp culture. Aquaculture, 543: 736969. DOI: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736969

|

|

Cornejo-Granados F, Gallardo-Becerra L, Leonardo-Reza M, et al. 2018. A meta-analysis reveals the environmental and host factors shaping the structure and function of the shrimp microbiota. PeerJ, 6: e5382. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.5382

|

|

Coyte KZ, Schluter J, Foster KR. 2015. The ecology of the microbiome: networks, competition, and stability. Science, 350(6261): 663–666. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad2602

|

|

Cui P, Zhou QC, Huang XL, et al. 2016. Effect of dietary vitamin B6 on growth, feed utilization, health and non-specific immune of juvenile pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture Nutrition, 22(5): 1143–1151. DOI: 10.1111/anu.12365

|

|

Dai WF, Chen J, Xiong JB. 2019. Concept of microbial gatekeepers: positive guys? Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 103 (2): 633–641.

|

|

D'Alvise PW, Magdenoska O, Melchiorsen J, et al. 2014. Biofilm formation and antibiotic production in Ruegeria mobilis are influenced by intracellular concentrations of cyclic dimeric guanosinmonophosphate. Environmental Microbiology, 16(5): 1252–1266. DOI: 10.1111/1462-2920.12265

|

|

Defoirdt T, Sorgeloos P, Bossier P. 2011. Alternatives to antibiotics for the control of bacterial disease in aquaculture. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 14(3): 251–258. DOI: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.004

|

|

Ding X, Jin F, Xu JW, et al. 2022. The impact of aquaculture system on the microbiome and gut metabolome of juvenile Chinese softshell turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis). iMeta, 1(2): e17. DOI: 10.1002/imt2.17

|

|

Dixon P. 2003. Vegan, a package of R functions for community ecology. Journal of Vegetation Science, 14(6): 927–930. DOI: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02228.x

|

|

Dong PS, Guo HP, Huang L, et al. 2023. Glucose addition improves the culture performance of pacific white shrimp by regulating the assembly of Rhodobacteraceae taxa in gut bacterial community. Aquaculture, 567: 739254. DOI: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.739254

|

|

Du Y, Xu WL, Wu T, et al. 2022. Enhancement of growth, survival, immunity and disease resistance in Litopenaeus vannamei, by the probiotic, Lactobacillus plantarum Ep-M17. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 129: 36–51.

|

|

Elzhov TV, Mullen KM, Spiess AN, et al. 2023. R interface to the levenberg-marquardt nonlinear least-squares algorithm found in MINPACK, Plus Support for Bounds: 1–14. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/minpack.lm/minpack.lm.pdf.

|

|

Evans S, Martiny JBH, Allison SD. 2017. Effects of dispersal and selection on stochastic assembly in microbial communities. The ISME Journal, 11(1): 176–185. DOI: 10.1038/ismej.2016.96

|

|

Falaise C, François C, Travers MA, et al. 2016. Antimicrobial compounds from eukaryotic microalgae against human pathogens and diseases in aquaculture. Marine Drugs, 14(9): 159. DOI: 10.3390/md14090159

|

|

FAO. 2022. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2022: towards blue transformation. www. fao. org.

|

|

Fraher MH, O'Toole PW, Quigley EMM. 2012. Techniques used to characterize the gut microbiota: a guide for the clinician. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 9(6): 312–322.

|

|

Goldford JE, Lu NX, Bajić D, et al. 2018. Emergent simplicity in microbial community assembly. Science, 361(6401): 469–474. DOI: 10.1126/science.aat1168

|

|

Guo HP, Dong PS, Gao F, et al. 2022. Sucrose addition directionally enhances bacterial community convergence and network stability of the shrimp culture system. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 8(1): 22. DOI: 10.1038/s41522-022-00288-x

|

|

Guo HP, Huang L, Hu ST, et al. 2020. Effects of carbon/nitrogen ratio on growth, intestinal microbiota and metabolome of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Frontiers in Microbiology, 11: 652. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00652

|

|

Han SY, Wang L, Wang YL, et al. 2020. Effects of the glutathione administration via dietary on intestinal microbiota of white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei, under cyclic hypoxia conditions. Invertebrate Survival Journal, 17(1): 36–50.

|

|

Harrell Jr FE. 2015. Hmisc: harrell miscellaneous. 235–236. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Hmisc/Hmisc.pdf.

|

|

Hernandez DJ, David AS, Menges ES, et al. 2021. Environmental stress destabilizes microbial networks. The ISME Journal, 15(6): 1722–1734. DOI: 10.1038/s41396-020-00882-x

|

|

Hoffmann A, Baltimore D. 2006. Circuitry of nuclear factor κB signaling. Immunological Reviews, 210(1): 171–186. DOI: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00375.x

|

|

Holt CC, Bass D, Stentiford GD, et al. 2021. Understanding the role of the shrimp gut microbiome in health and disease. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 186: 107387. DOI: 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107387

|

|

Hong WD, Lin SH, Zippi M, et al. 2017. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood urea nitrogen, and serum creatinine can predict severe acute pancreatitis. BioMed Research International, 2017: 1648385.

|

|

Jaber BA, Majeed KR, AL. hashimi A G. 2021. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of β-carotene pigment extracted from Parococcus homiensis strain BKA7 isolated from air of basra, Iraq. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 25(4): 14006–14028.

|

|

Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, et al. 2019. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature Biotechnology, 37(8): 907–915. DOI: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4

|

|

Knights D, Kuczynski J, Charlson ES, et al. 2011. Bayesian community-wide culture-independent microbial source tracking. Nature Methods, 8(9): 761–763. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.1650

|

|

Koga A, Goto M, Hayashi S, et al. 2022. Probiotic effects of a marine purple non-sulfur bacterium, Rhodovulum sulfidophilum KKMI01, on kuruma shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus). Microorganisms, 10(2): 244. DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms10020244

|

|

Lee J, Roh SW, Whon TW, et al. 2011. Genome sequence of strain TW15, a novel member of the genus Ruegeria, belonging to the marine Roseobacter clade. Journal of Bacteriology, 193(13): 3401–3402. DOI: 10.1128/JB.05067-11

|

|

Lin WC, He YM, Li RH, et al. 2023. Adaptive changes of swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus) associated bacteria helping host against dibutyl phthalate toxification. Environmental Pollution, 324: 121328. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121328

|

|

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology, 15(12): 550. DOI: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

|

|

Merrifield DL, Ringo E, 2014. Aquaculture Nutrition: Gut Health, Probiotics, and Prebiotics. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. , 53–74.

|

|

Montesinos-Navarro A, Hiraldo F, Tella JL, et al. 2017. Network structure embracing mutualism–antagonism continuums increases community robustness. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1(11): 1661–1669.

|

|

Newaj-Fyzul A, Al-Harbi AH, Austin B. 2014. Review: developments in the use of probiotics for disease control in aquaculture. Aquaculture, 431: 1–11. DOI: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.08.026

|

|

Nichols RG, Davenport ER. 2021. The relationship between the gut microbiome and host gene expression: a review. Human Genetics, 140(5): 747–760. DOI: 10.1007/s00439-020-02237-0

|

|

Östman Ö, Drakare S, Kritzberg ES, et al. 2010. Regional invariance among microbial communities. Ecology Letters, 13(1): 118–127. DOI: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01413.x

|

|

Pan Z, Ma T, Steele M, et al. 2024. Varied microbial community assembly and specialization patterns driven by early life microbiome perturbation and modulation in young ruminants. ISME Communications, 4(1): ycae044. DOI: 10.1093/ismeco/ycae044

|

|

Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, et al. 2011. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. The Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12: 2825–2830.

|

|

Peng GS, Wu J. 2016. Optimal network topology for structural robustness based on natural connectivity. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 443: 212–220. DOI: 10.1016/j.physa.2015.09.023

|

|

R Core Team. 2016. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

|

|

Refaeilzadeh P, Tang L, Liu H. 2009. Cross-validation. In: Liu L, Tamer Özsu M. Encyclopedia of Database Systems. New York: Springer, 532–538.

|

|

Richards AL, Muehlbauer AL, Alazizi A, et al. 2019. Gut microbiota has a widespread and modifiable effect on host gene regulation. mSystems, 4(5): e00323–18.

|

|

Sadat Hoseini Madani N, Adorian TJ, Ghafari Farsani H, et al. 2018. The effects of dietary probiotic bacilli (Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis) on growth performance, feed efficiency, body composition and immune parameters of whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) postlarvae. Aquaculture Research, 49(5): 1926–1933. DOI: 10.1111/are.13648

|

|

Sanchez G, Trinchera L, Russolillo G. 2024. Plspm: partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM). http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=plspm.

|

|

Sha HN, Lu JQ, Chen J, et al. 2024. Rationally designed probiotics prevent shrimp white feces syndrome via the probiotics-gut microbiome-immunity axis. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 10(1): 40. DOI: 10.1038/s41522-024-00509-5

|

|

Sha HN, Zhang XX, Chen J, et al. 2025. Prophylactic sarafloxacin hydrochloride increases shrimp susceptibility to ahpnd via transferring antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors. Aquaculture, 603: 742379.

|

|

Simon M, Scheuner C, Meier-Kolthoff JP, et al. 2017. Phylogenomics of rhodobacteraceae reveals evolutionary adaptation to marine and non-marine habitats. The ISME Journal, 11(6): 1483–1499. DOI: 10.1038/ismej.2016.198

|

|

Sloan WT, Lunn M, Woodcock S, et al. 2006. Quantifying the roles of immigration and chance in shaping prokaryote community structure. Environmental Microbiology, 8(4): 732–740. DOI: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00956.x

|

|

Sonnenschein EC, Nielsen KF, D'Alvise P, et al. 2017. Global occurrence and heterogeneity of the Roseobacter-clade species Ruegeria mobilis. The ISME Journal, 11(2): 569–583. DOI: 10.1038/ismej.2016.111

|

|

Tellier A, de Vienne DM, Giraud T, et al. 2010. Theory and examples of reciprocal influence between hosts and pathogens, from short-term to long term interactions: Coevolution, cospeciation and pathogen speciation following host shifts. In: Barton AW. Host-Pathogen Interactions: Genetics, Immunology, and Physiology. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. , 37–78.

|

|

Vadstein O, Attramadal KJK, Bakke I, et al. 2018. K-selection as microbial community management strategy: a method for improved viability of larvae in aquaculture. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9: 2730. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02730

|

|

Wahlström A, Sayin SI, Marschall HU, et al. 2016. Intestinal crosstalk between bile acids and microbiota and its impact on host metabolism. Cell Metabolism, 24(1): 41–50. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.005

|

|

Wang JJ, He TT, Chen L, et al. 2024. Antibacterial efficiency of the curcumin-mediated photodynamic inactivation coupled with L-arginine against Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its application on shrimp. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 411: 110539. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2023.110539

|

|

Wang WL, Ishikawa M, Koshio S, et al. 2018. Effects of dietary astaxanthin supplementation on juvenile kuruma shrimp, Marsupenaeus japonicus. Aquaculture, 491: 197–204. DOI: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.03.025

|

|

Wang YT, Wang K, Huang L, et al. 2020a. Fine-scale succession patterns and assembly mechanisms of bacterial community of Litopenaeus vannamei larvae across the developmental cycle. Microbiome, 8(1): 106. DOI: 10.1186/s40168-020-00879-w

|

|

Wang T, Shan HW, Geng ZX, et al. 2020b. Dietary supplementation with freeze-dried Ampithoe sp. Enhances the ammonia-N tolerance of Litopenaeus vannamei by reducing oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress and regulating lipid metabolism. Aquaculture Reports, 16: 100264. DOI: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2019.100264

|

|

Wu GY. 2009. Amino acids: metabolism, functions, and nutrition. Amino Acids, 37(1): 1–17. DOI: 10.1007/s00726-009-0269-0

|

|

Xiao FS, Zhu WG, Yu YH, et al. 2021. Host development overwhelms environmental dispersal in governing the ecological succession of zebrafish gut microbiota. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 7(1): 5.

|

|

Xie SW, Tian LX, Jin Y, et al. 2014. Effect of glycine supplementation on growth performance, body composition and salinity stress of juvenile pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei fed low fishmeal diet. Aquaculture, 418 – 419 : 159–164.

|

|

Xie SW, Tian LX, Li YM, et al. 2015. Effect of proline supplementation on anti-oxidative capacity, immune response and stress tolerance of juvenile Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture, 448: 105–111.

|

|

Xiong JB, Zhu JY, Dai WF, et al. 2017. Integrating gut microbiota immaturity and disease-discriminatory taxa to diagnose the initiation and severity of shrimp disease. Environmental Microbiology, 19(4): 1490–1501. DOI: 10.1111/1462-2920.13701

|

|

Xiong JB, Dai WF, Qiu QF, et al. 2018. Response of host-bacterial colonization in shrimp to developmental stage, environment and disease. Molecular Ecology, 27(18): 3686–3699. DOI: 10.1111/mec.14822

|

|

Xiong JB, Sha HN, Chen J. 2024. Updated roles of the gut microbiota in exploring shrimp etiology, polymicrobial pathogens, and disease incidence. Zoological Research, 45(4): 910–923.

|

|

Xu ZF, Li ML, Wang YY, et al. 2023. Affecting mechanism of Chlorella sorokiniana meal replacing fish meal on growth and immunity of Litopenaeus vannamei based on transcriptome analysis. Aquaculture Reports, 31: 101645. DOI: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2023.101645

|

|

Yang G, Xu ZJ, Tian XL, et al. 2015. Intestinal microbiota and immune related genes in sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) response to dietary β-glucan supplementation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 458(1): 98–103.

|

|

Yang W, Zheng ZM, Lu KH, et al. 2020. Manipulating the phytoplankton community has the potential to create a stable bacterioplankton community in a shrimp rearing environment. Aquaculture, 520: 734789.

|

|

Zhang J, Liu YJ, Tian LX, et al. 2013. Effects of dietary astaxanthin on growth, antioxidant capacity and gene expression in pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture Nutrition, 19(6): 917–927.

|

|

Zhang SS, Liu S, Liu HW, et al. 2024. Stochastic assembly increases the complexity and stability of shrimp gut microbiota during aquaculture progression. Marine Biotechnology, 26(1): 92–102.

|

|

Zhang XJ, Yuan JB, Sun YM, et al. 2019. Penaeid shrimp genome provides insights into benthic adaptation and frequent molting. Nature Communications, 10(1): 356.

|

|

Zhou JZ, Ning DL. 2017. Stochastic community assembly: does it matter in microbial ecology? Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 81 (4): e00002–17.

|